Blog post by IHRC students Sophie McEvoy, Cassandra Wilkins, and Ella Wesly

Logo of the UN CEDAW Committee

The International Human Rights Clinic at Santa Clara Law (“IHRC”) submitted a written contribution for consideration by the United Nations during a general discussion on protecting indigenous women’s rights. In its submission, the IHRC’s recommends that States Parties to the UN Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (“CEDAW”) implement measures to protect indigenous women from violence, lack of access to justice, and lack of access to education, labor, healthcare, and basic necessities. The IHRC’s submission can be viewed here: Day of General Discussion on the Rights of Indigenous Women and Girls.

The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (“CEDAW Committee”) held the discussion on Thursday, June 24, 2021, during its 79th session. The discussion focused on two themes: “equality and non-discrimination with a focus on indigenous women and girls and intersecting forms of discrimination” and “effective participation, consultation and consent of indigenous women and girls in political and public life”.

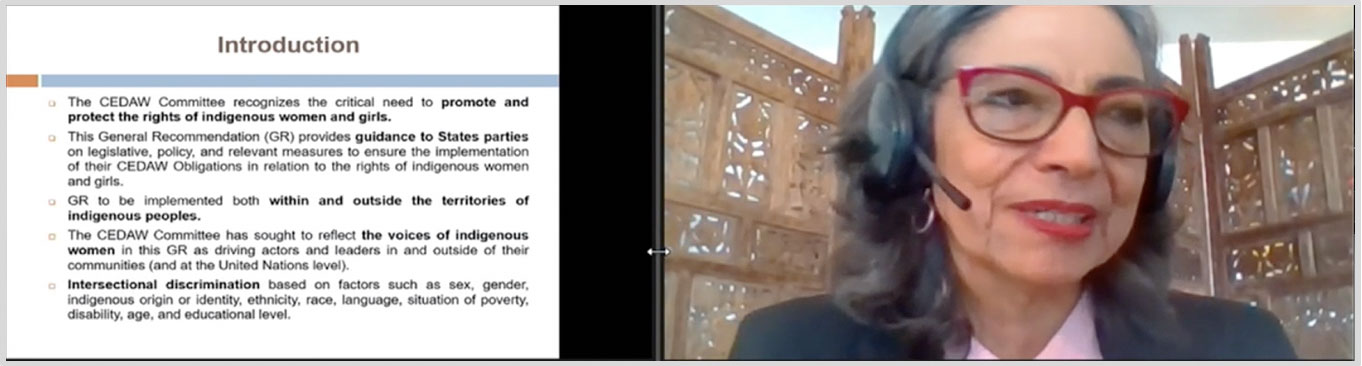

Screenshot of Gladys Acosta, Expert for the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, introducing the topic at the Day of General Discussion

The Committee’s goal was to spark debate about how indigenous women face discrimination and to seek input on what measures States should adopt to be fully compliant with CEDAW.

CEDAW, adopted by the UN in 1979, consists of 30 articles defining and describing what constitutes discrimination against women. Discrimination is defined as “any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field.”

Although CEDAW has been widely ratified by most countries, meaning that they are bound by the Convention’s articles, the United States remains one of very few States that have not ratified this treaty. However, the remaining States that are bound by the treaty must comply with its measures, and these recommendations will provide more guidance on how to do so.

As stated previously, the IHRC focused on three major topics relating to indigenous women’s rights: violence in armed conflicts and extractive projects, lack of access to justice, and basic necessities.

II. Violence in Armed Conflict & Extractive Projects

Indigenous women face violence under contexts where State and non-State actors seek to establish control over indigenous territories and economic resources. While the IHRC discussed numerous situations where indigenous women are particularly vulnerable to violence, our submission focused on two specific contexts: violence in armed conflict and violence in extractive projects. These two contexts effectively recognize a recolonization of indigenous territories that is often accompanied by a third context discussed by the IHRC: militarization of indigenous lands.

As a result of armed conflict and extractive projects, indigenous women become especially vulnerable to sex-based atrocities, such as rape and sexual assault, inflicted by soldiers, paramilitary troops, and the employees and security guards of companies investing in these territories. The Clinic’s submission cites specific examples of violence rendered against indigenous women in Guatemala (where Mayan women were subjected to atrocities as part of a military-led campaign to destroy the community’s social order and cultural identity) and Suriname (where indigenous women living near gold mines suffer from reproductive health issues from exposure to mercury).

Many of these violent acts against indigenous women still go unreported. Apart from the lack of access to social services, indigenous women also risk facing rejection and ostracism from their own communities, if they report any crimes of sexual violence. To that end, the Clinic urged CEDAW to take note of the intersectionality of these contexts of violence and recommend measures that account for that intersectional nature.

II. Lack of Access to Justice

Second, the IHRC’s submission addressed how indigenous women do not have proper access to justice, which is due in part to their lack of basic legal education, interpreters, and monetary resources, and their geographic isolation.

Indigenous women often live far away from courthouses, requiring them to walk several days to file a complaint. Further, they sometimes will not speak the same language, and may not have access to a translator. However, even if a translator is provided, the translator may not understand the culture, norms, and values of indigenous women. To ensure better access to justice, the IHRC recommends that States provide professionals such as health care workers and translators with information regarding the culture and particular needs and circumstances of indigenous women.

Additionally, the IHRC recommends that States allow indigenous women to actively participate in the determination of forms of reparations for human rights violations committed against them. Participation allows indigenous women to take back their bodily autonomy. Reparations should not only focus on the individual, but also must aim to dismantle the systemic violence that indigenous women face and enact societal and cultural transformations.

Finally, the IHRC suggests that States take affirmative measures to address high rates of poverty among indigenous women and girls, limited access to proper infrastructure, and minimal consideration of their culture, languages, and needs, as it affects their access to education, work, healthcare, and basic necessities.

III. Basic Necessities

Education & Labor

Third, IHCR’s written contribution addressed how indigenous women and girls’ lack of adequate education has a detrimental effect on their right to labor. The United Nations has addressed the fact that primary education is one of the main indicators of future access to the labor market and to vital benefits such as social security.

Significant contributing factors of limited education are insufficient consideration of indigenous cultural expectations and lack of infrastructure. Cultural expectations include proper bilingual programs that address cultural dynamics within indigenous communities. When school classes are not taught in indigenous languages or schools are not built near the rural locations in which indigenous girls often live, this vulnerable population often opts to live as caretakers or enter into early motherhood, thus limiting their work opportunities. Supporting more bilingual and widespread education programs are important steps to support the rights of indigenous women and girls to education and labor.

Healthcare

In addition to the low rates of education among indigenous women and girls, there is also low accessibility to proper healthcare. The American Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recognizes that all indigenous peoples have the “collective and individual right” to the highest possible standard of “physical, mental, and spiritual health.” However, these issues are not adequately addressed when it comes to indigenous women.

With limited infrastructure for healthcare, indigenous women are repeatedly left in a disproportionately vulnerable state. Across the Americas, for example, indigenous populations suffer because health centers are often either many hours away, culturally inappropriate, or lack proper interpreters. As a result of these factors, Mexican indigenous women, for example, have a nine-times higher rate of infant mortality than the rest of the population. Brazil also reports that the highest rates of infant mortality are among their indigenous communities. To improve access to basic needs for indigenous women and girls, there must be improvement in the infrastructural support.

IV. Conclusion

With all these issues in mind, the IHRC invited the CEDAW Committee to recommend that States Parties to CEDAW adopt additional safeguards to protect indigenous women and girls from violence and to promote better access to justice, education, labor, and healthcare.