Santa Clara Law student Heather G. Fuchs

Last semester, Santa Clara Law’s International Human Rights Clinic submitted comments to the United Nation’s Open-ended Intergovernmental Working Group on Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with Respect to Human Rights (OEIGWG or “Working Group”). The comments highlight specific recommendations for the Working Group to add clarification and improve definitions during the ongoing drafting process of a new treaty, which addresses the relationship between business activity and human rights.

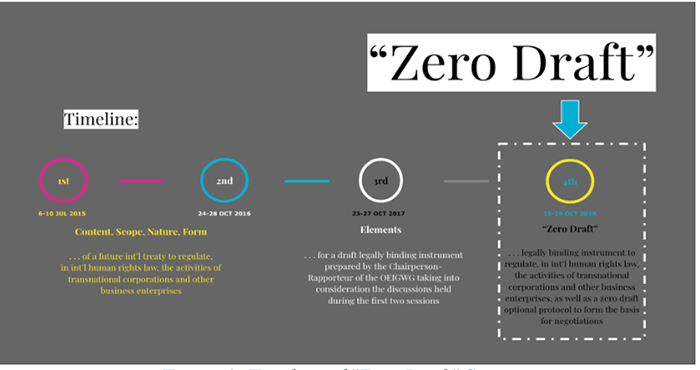

The Working Group was established in 2014 by the Human Rights Council and mandated “to elaborate an international legally binding instrument on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights.” In the First and Second Sessions, the Working Group discussed the content, scope, nature, and form of the working treaty, before deciding on key Elements in the Third Session. Born out of these discussions was the Legally Binding Instrument to Regulate, in International Human Rights Law, the Activities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises (or “Zero Draft”), which was presented by the Permanent Mission of Ecuador on behalf of the Chairmanship of the Working Group. The Working Group met again in October 2018 at its Fourth Session to discuss the Zero Draft, as well as the Optional Protocol which was subsequently annexed to the treaty.

Timeline of “Zero Draft” Sessions

This is not the first time the international human rights community has attempted to bring corporate accountability to the human rights realm. In June 2008, Professor John Ruggie, United Nations Special Representative on “transnational corporations and other business enterprises with regard to human rights,” presented a framework for business and human rights to the Human Rights Council which included three main pillars:

- State duty to protect against human rights violations by third parties (including businesses);

- Corporate responsibility to respect human rights; and,

- Greater access for victims to effective remedies.

In March 2011, Professor Ruggie expanded upon this framework and issued “Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy’ Framework.” In June 2011, these Guiding Principles were unanimously adopted by the Human Rights Council. The Guiding Principles, which are non-binding, received widespread support among States, businesses, and civil society. Despite this support, however, little has since been achieved by way of binding international law. The Working Group’s Zero Draft seeks to change that by imposing legally binding obligations upon businesses.

European Union Delegate Comments During the 4th Session in October 2018

The Clinic’s comments address articles 1, 3, and 4.2 of the Zero Draft, as well as the Optional Protocol. While the Zero Draft provides a welcome framework for developing a legally binding treaty to regulate business-related activity by transnational corporations and other business enterprises and places due emphasis on victims’ access to remedies, its failure to adequately define the overall scope and certain crucial terms in its text has far-reaching implications. The Zero Draft, as it currently stands, could threaten the ability to build State consensus for the treaty’s ratification and may impose a negative impact on smaller businesses, whose role in this context is murkily defined. This treaty would largely benefit from several simple clarifications:

- Explain which human rights would form the basis of this treaty;

- Define which types of businesses should be held accountable; and,

- Establish a concrete remedy scheme for individual communications in the body of the treaty, rather than the Optional Protocol alone.

Comments from participating Member States and NGOs at the Fourth Session (webcast; draft report – under “Documents”) address similar issues to those submitted by the Clinic. Participants requested more polished definitions; for example, drop the term “all” when referring to businesses and address only transnational corporations and define “transnational activity” in a way that considers contractual links, parent companies, and global supply chains. Additionally, contributors suggested that the treaty adopt a minimum core of human rights, leaving the decision to establish greater protections up to the States.

Professor Ruggie has warned against “going down a road that would end in largely symbolic gestures, of little practical use to real people in real places, and with a high potential for creating serious backlash against any form of further international legalization in this domain.” By refining key terms and defining the treaty’s scope, the Working Group would honor Professor Ruggie’s foundational work in this arena and might garner more widespread support across multiple stakeholders with diverging interests.