By Professor Margaret M. Russell

This article is part of a series on issues surrounding the replacement of Associate Justice Antonin Scalia. View other articles in this series.

Shortly after Associate Justice Antonin Scalia’s death on Saturday, February 13, political discussion erupted with unsettling speed over whether President Barack Obama should nominate a replacement and what type of justice that eventual replacement should be. Justice Scalia, the most prominent and outspoken conservative on a closely divided Court, was a hero to most if not all of the Republican candidates. They stressed the importance of continuing his thirty-year legacy

At that night’s Republican presidential debate in South Carolina, CBS news correspondent John Dickerson’s first question for the candidates was about President Obama and the nomination process:

Dickerson: First, the death of Justice Scalia, and the vacancy that leaves on the Supreme Court. Mr. [Donald] Trump, I want to start with you. You’ve said that the President shouldn’t nominate anyone in the rest of his term to replace Justice Scalia. If you were President, and had a chance with 11 months left to go in your term, wouldn’t it be an abdication to conservatives in particular, not to name a conservative justice with the rest of your term?

Trump: Well, I can say this. If the President, and if I were President now I would certainly want to try and nominate a justice. I’m sure that, frankly, I’m absolutely sure that President Obama will try to do it. … I think he’s going to do it whether I’m OK with it or not. I think it’s up to Mitch McConnell [U.S. Senate Majority Leader] and everybody else to stop it. It’s called delay, delay, delay.

There is no hiding the ball here. It is a nasty presidential election year with a deeply divided electorate. “Delay, delay, delay” is hardly a new strategy in blocking judicial nominations. In widely varying degrees over the last three decades, both Republicans and Democrats have fought tough ideological battles over the direction of the Court, as well as the lower federal district courts and courts of appeal. But refusal to schedule hearings for or even meet any Supreme Court nominee is a level of obstruction that insults the people of this country and the constitutional process.

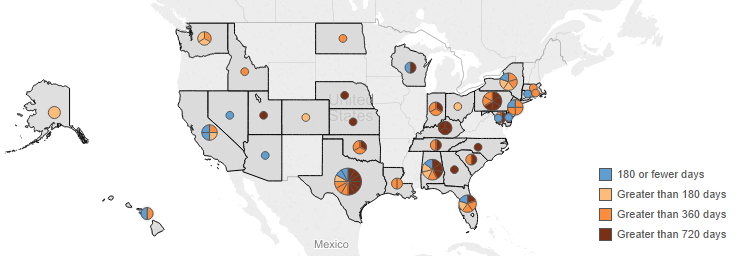

This year, the numbers reveal that we have hit a new low in judicial vacancies at all levels of the federal courts. This dysfunction of the federal court system is caused by failure to approve or even consider nominees; it has crisis-level implications for the administration of justice. The Alliance for Justice, which compiles up-to-date statistics on vacancies and nominations in the federal judiciary, reports that only 11 judicial nominations were approved in 2015, leaving approximately 70 vacancies in the federal district courts and courts of appeal. This number of confirmations is below that of any other Senate in over 50 years.

AFJ Judicial Selection Dashboard showing days since vacancy announcements. Via http://www.afj.org/judicial-selection-dashboards

Our national discourse and Senatorial game-playing are deteriorating rapidly. Article II, Section 2, paragraph 2 of the U.S. Constitution provides that the President “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint…Judges of the Supreme Court.” Sharply contested nominees have at least had the opportunity to be heard at some level; for example, when President George W. Bush nominated White House Counsel Harriet Miers in 2005 to fill the seat of Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, Miers at least had the opportunity for interviews with the Republican-led Senate Judiciary Committee before bipartisan opposition resulted in the withdrawal of her nomination. For the current Republican members of the Senate Judiciary Committee to vote unanimously to block all stages of a confirmation hearing is, quite simply, shocking and extremely deleterious to the work of justice. A great deal of “tit-for-tat” argumentation and precedent-finding are occurring on all sides of the debate. The bottom-line fact remains that it is the American people who suffer from an extended period with an eight-justice Court.

This reality has been recognized by justices, regardless of the Presidents that appointed them. In Cheney v. U.S. District Court, 541 U.S. 913 (2004), Justice Scalia explained his decision not to recuse himself from a case involving Vice-President Dick Cheney, with whom Scalia had gone hunting in 2002. Scalia noted the inefficacy of decision-making with an eight-person Court, particularly if a lower court decision would be “affirmed by an equally-divided Court” (in other words, 4 to 4). Separately, John Roberts and William Rehnquist, as chief justices responsible for the administrative leadership of the entire federal court system in accordance with federal statute, well recognized the practical diminution of function caused by any judicial vacancies, particularly at the Supreme Court level. The current imbroglio is not just political football or an amusing guessing-game: it is a serious blow to the work of the courts.

Left, right, or center, it is time for the American people to demand greater accountability from the Senate in filling judicial vacancies, beginning with the current vacancy on the Supreme Court. Constitutionally, the Senate has the power to refuse to confirm as part of its “advice and consent”; refusing to consider nominees at all is a dereliction of duty.