by Professor David L. Sloss

This article is part of a series on issues surrounding the replacement of Associate Justice Antonin Scalia. View other articles in this series.

The sudden death of Justice Antonin Scalia has sparked the most important election-year battle over a Supreme Court nomination since 1968. In June 1968, Earl Warren informed President Lyndon Johnson that he intended to resign his position as Chief Justice. Johnson had previously announced that he would not be seeking re-election. Even so, Johnson recognized an opportunity to secure his legacy. He quickly nominated Associate Justice Abe Fortas to replace Warren as Chief Justice. He also nominated Judge Homer Thornberry to fill Fortas’s seat as an Associate Justice.

President Lyndon B. Johnson and Abe Fortas. Via https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abe_Fortas#/media/File:LBJ_and_Abe_Fortas.jpg

Thanks to a lengthy filibuster, the Senate never voted on Fortas’ nomination. Ultimately, in October 1968, Fortas asked Johnson to withdraw his nomination when it became apparent that he would not be confirmed. Once Fortas was defeated, the Thornberry nomination also died. Richard Nixon, the Republican Presidential nominee, played a key behind-the-scenes role in blocking Fortas’s appointment. As is well known, Nixon went on to win the Presidential election. Perhaps less well known, though, is the impact of that election on the Supreme Court.

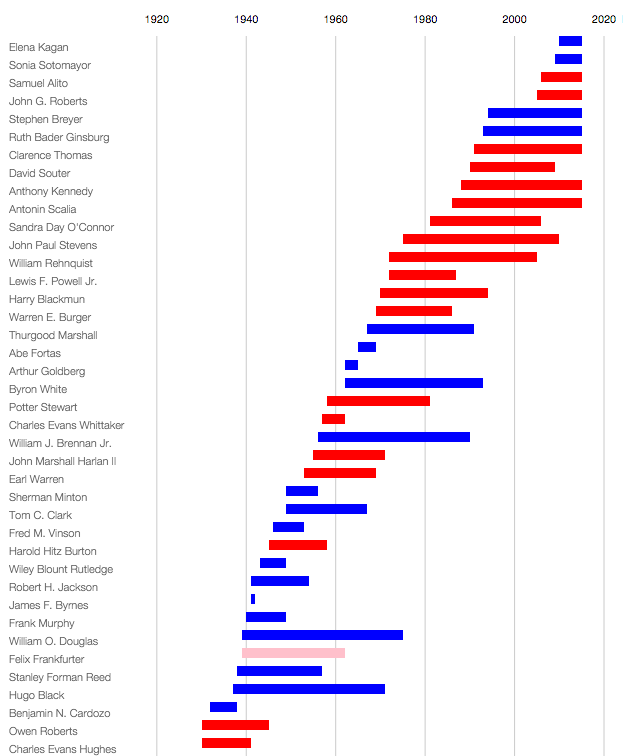

During the 1968 Presidential campaign, Nixon promised to appoint conservative Supreme Court Justices. He delivered on that promise. Nixon appointed four new Justices between 1969 and 1972—more than any other President since Eisenhower. Warren Burger replaced Earl Warren as Chief Justice in 1969. Harry Blackmun, Lewis Powell and William Rehnquist replaced Abe Fortas, Hugo Black and John Harlan in 1970-72. If the Senate had voted to confirm Fortas and Thornberry in 1968, the Supreme Court in the 1970s and early 1980s would probably have resembled the liberal Warren Court of the 1950s and 60s. Instead, the Burger Court of the 1970s and 1980s was ideologically similar to the conservative Rehnquist Court of the 1990s. The legacy of the Nixon appointments is clear: we have had a conservative majority on the Supreme Court since 1972.

Supreme Court Justice appointments from 1930 to present. Legend: Democrat – blue; Republican – red; Independent – pink. Chart generated via http://jalapic.github.io/justice#

This brief history provides important lessons for both parties. President Obama has an opportunity to create a liberal majority on the Supreme Court for the first time since 1972. Lyndon Johnson squandered his opportunity by nominating people who were perceived to be ultra-liberal political cronies of the President. President Obama would be well advised to nominate someone who is perceived as a moderate, rather than a liberal. He should avoid any nomination that might be viewed as “payback” for past political favors.

Senate Republicans defeated Fortas’ nomination by joining forces with conservative Southern Democrats. If Obama makes a smart nomination, Senate Democrats in 2016 will present a united front in support of his nominee. If Republicans present a united front against Obama’s nominee, they have the power to block his or her appointment. However—given the recent announcement that Senate Republicans refuse even to meet with any Obama nominee—the Republican Party will probably pay a political cost at the polls in November for engaging in blatant obstructionism.

The stakes are very high. If Obama’s nominee is confirmed (which seems improbable at the moment), we will likely see several important changes in constitutional law over the next few years. The Supreme Court was on the verge of dealing a death blow to affirmative action programs before Justice Scalia died. A Court with a 5-4 liberal majority would likely revive affirmative action. The Court has imposed strict, new constitutional limits on gun control legislation in the past decade. A Court with a liberal majority would probably relax constitutional constraints on the power of state and local governments to enact tough gun control measures. In recent years, the Supreme Court has erected new constitutional constraints on campaign finance reform. A more liberal Court would probably give both state and federal governments greater leeway to regulate the influence of money on election campaigns.

Given what is at stake, no one should be surprised that the fight over a potential replacement for Justice Scalia has much in common with mud wrestling. That is the nature of democratic politics. We can only hope that the nomination battle produces a new Supreme Court Justice who has both wisdom and integrity.